Home List of Contents Links Contact Wood and Water The Labyrinth of the Heart |

|

|

|

He came to our city looking for employment. It was soon clear that he had a wide knowledge of many languages, and most of our merchants began to employ him in their dealings with foreign traders. We saw him speeding from one to another, in those sandals of his with the odd widening at the heels, often pausing to tell one merchant of a recent purchase of interest by another. It seemed that trade prospered with his coming. Our merchants became wealthier and busier than they had ever been. Strangely enough, though, it seemed that the city's thieves also prospered. There were more daring burglaries, more pockets picked on an empty street, than ever before. But this actually added to the city's sense of life, as it all happened without any increase in violence. His work was so good that we asked him to interpret for several diplomatic missions. Once again we seemed to get the better of the deals, though the foreigners seemed pleased, too. We grew used to seeing him in all parts of the city, using his staff to emphasise points, or bringing it down with a thump when deals were concluded. We admired the spiral decorations running round it — sometimes they seemed to us to be moving, but that was surely no more than a trick of the light. The trouble arose when we decided that such a cultured man deserved to learn about our religion and the truths it contained.

We showed him one of our sacred scrolls,

written in the old language, and we were not a bit surprised when he

was able to read and translate it without difficulty. We asked him to expound to us further. He did so for some time, and then we were surprised to hear him ask "Why were cows so important to your people in the old days?" "But they weren't" we protested, "cows aren't even mentioned in the sacred books". "That reminds me of the curious incident of the dog in the night-time" was his puzzling reply. "What dog? What night-time?" "Oh, never mind," he said, "I was thinking of an occasion far away in time and space from here".

"But what about the cows," we persisted.

"Your people of old included many farmers, and farming is still

important to you." "Of course." "And your farms contain

horses, sheep, pigs, and cattle, as well

as chickens and plants." "Certainly." "Then why do your texts speak

of horses, sheep, and pigs, and yet they make no mention of cattle

and those who farm them."

By now he was talking each week in the

main square. One day we noticed an unusually large number of sailors

among the crowds. We were surprised, as they had not been greatly

involved in the past, but we did not expect that

we were seeing the beginning of real trouble. The interpreter began

to speak of the sea, and we assumed that the sailors had attended

because of some rumour that this might happen. He stopped at that point, and we all felt we had much to ponder on. We were not surprised to find even more sailors in the crowd the next week. "Why," he began, "since sailors and the sea are so important to you, are sailors not permit to officiate in temple ceremonies." We explained to him that sailors are always travelling, and cannot be relied upon to be at the temples at the proper times. "But your merchants travel also in search of new goods and markets, and there is no restriction on them." "That's different," we explained to him at once, "Merchants are settled people, and if one can't be present on some occasion, there is always someone else available for the ceremonies." "Then couldn't the same be done for sailors." Once again we explained to him that that was different, but he remained obstinately unable to see any difference.

By that time the sailors were restless.

Some of them suddenly unfurled a banner demanding that sailors

should have the right to conduct sacrifices on behalf of the people.

We hastily declared the day's session closed, and called in the

military to persuade people to leave the square quietly.

"Why did you do this?" we asked as we pushed him out of the city's main gate. "If you don't know why change was needed, ask the sailors. Let them write the texts not yet written, let them speak the prophecies not yet spoken. As for myself, where you saw stability I saw sterility. I acted so that you who were high-ranking and powerful would learn that rank and power were not theirs by right, and so that you would find the world turned upside down."

"And besides," he added, "I thought it

might be an Improoovement."

Wood and Water

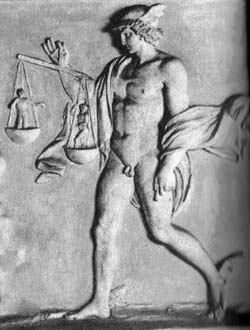

44, Autumn 1993 Notes The Greek god Hermes, trickster and lord of language, likes puns. This story had its origin in the pun in the last line and the subtitle. Hermes is also the god of thieves, merchants, and diplomacy, and wears winged sandals and carries a staff with snakes. The story includes all these aspects. The word 'hermeneutics' is from a Greek word meaning 'interpreter', which in turn is derived from the role of Hermes as deity of speech, writing, and trade. It is the art of interpretation, especially of the scriptures. The account given in the story does cover some basic hermeneutical techniques. Some of the ideas in the story were suggested by two of Elizabeth Schussler Fiorenza's academic books on feminist hermeneutics, But SHE Said and Bread, not Stone. Rabbi Malka Drucker (in the July 1st, 2003, issue of the online magazine Awakened Woman) expresses the idea that every text contains two messages by saying: "An ancient Jewish commentary describes sacred text as "black fire written upon white fire." Black tells one story, white another. We can only read the first story, but one day we will know both narratives, and on that day, when we have the whole story, we'll know how to live in peace." She suggests that the white fire, the part that has been neglected, is "the other story, the "white fire" that reveals the divine through women's lives as creators and nurturers of life." I discovered two relevant quotations after I had begun the story, which I feel was a gift from Hermes. The sentences "But then I read ...to be received" are by Lynn Gottlieb (The Secret Jew in On Being A Jewish Feminist), while the passage about landfolk comes (with a small but significant change) from A.S. Byatt's Angels and Insects. Very many thanks to A. S. Byatt for allowing me to include this long quotation in my text, and thanks also to Malka Drucker and Lynn Gottlieb for allowing me to use their words. Rimble, the Trickster god who is the central character of Zohra Greenhalgh's fantasy novel, Contrarywise, asked me to be sure to mention his favourite notion, that of an 'Improoovement'. I wanted to pay homage to this other trickster god by using this word rather than just referring to an 'improvement'. In Arthur Conan Doyle's The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes, in the case of Silver Blaze, we find the following remarks. "[I draw your attention to]

the curious incident of the dog in the night-time." Though this occurred far distant in time and place from the city of our story, it is very like the interpreter's insistence that we pay attention to what is omitted from a text as well as to what is included. The controversy over sailors and their role in the temple was suggested by the recent controversy in the Church of England over ordination of women. Do you think the story is too male-dominated, with its mention of farmers, merchants, and sailors? If so, use some hermeneutical analysis. The only character whose gender is mentioned is the interpreter himself.

Home List of Contents Links Contact Wood and Water The Labyrinth of the Heart All images: Artists unknown

|